Key finding

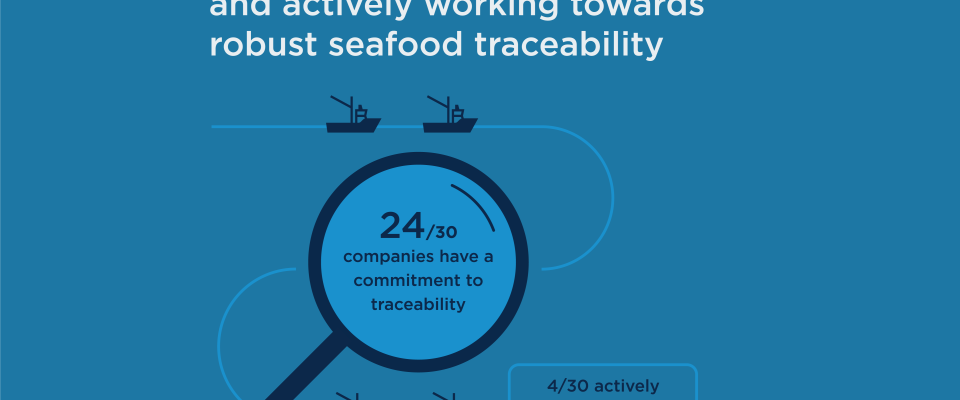

More companies commit to traceability but remain vague on concrete progress

Seafood traceability, the ability to track seafood products and its attributes (e.g., origin, harvest date, gear used) from point of harvest to point of final sale, is key to combat fraud and prevent illegally caught products from entering supply chains. Traceability can also help reduce costs and increase margins for seafood processors through benefits such as fewer product recalls, lower product waste and lower legal costs. Furthermore, research conducted by Planet Tracker in 2022 showed that if traceability were implemented in all species and areas where it is currently feasible, it would lead to a 60% increase in the global profit pool and a USD 600 billion increase in valuation of global seafood supply chain corporates.

One of the main barriers to industry-wide traceability is a lack of interoperability between companies which is in turn due to system incompatibility, poor data capture and management, and traceability gaps in the supply chain. Seeking to address this challenge, in March 2020 the Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability (GDST) launched a set of traceability standards that are open-source, non-proprietary and based on a common digital language. Widescale implementation of the GDST standards would drastically reduce the lack of interoperability between companies along the supply chain and encourage better data capture and management.

Commitment to traceability

Many large retailers have already pledged to adopt and implement these standards. Yet, although 12 out of the 30 largest companies in the seafood sector have endorsed the GDST standards since they were released, only one company (Nueva Pescanova) has a time-bound commitment to implement them.

Implementation of interoperable traceability systems

In terms of implementation, our results show that 9 companies (Bolton Group, Cargill, High Liner, Labeyrie Fine Foods, Nueva Pescanova, Nutreco (Skretting), Parlevliet Royal Greenland and Thai Union) disclose which key data elements they collect and provide an explanation of how these are verified and shared along the supply chain, while only four of those companies demonstrate they are actively working towards implementing the GDST standards (Labeyrie Fine Foods, Thai Union, Cargill and Nueva Pescanova). Two companies (Trident Seafood and Nomad Foods) demonstrate have more than 80% of their seafood portfolio Chain of Custody certified which guarantees some level of traceability, ensuring that certified products are separate from non-certified products and that a record of ownership is maintained along the supply chain. However, Chain of Custody certification does not require interoperability, nor does it allow for a rapid access to traceability data.

In summary, too few companies have so far made a commitment to the GDST standards – let alone a time-bound plan to implement them – and over two thirds of the companies assessed still do not disclose details such as the proportion of their portfolio covered by traceability solutions, the key data elements that are collected, or how far back in the supply chain the traceability system traces the relevant information. Seafood companies must tackle this challenge head-on. Without this transparency, it is not possible to understand how the largest companies are progressing and leading the way towards robust traceability in seafood supply chains, the backbone to legal, sustainable and ethical seafood production.