The sustainability skill gap in the boardroom: how can companies bridge it?

The boardroom’s traditional focus on generating wealth for its shareholders is gradually shifting towards generating value for all its stakeholders. New skills and expertise are required for boards to remain competent and fit-for-purpose as sustainability expectations keep rising. Times are changing, but are boards ready?

As Paul Polman, WBA Ambassador, business leader and former CEO of Unilever, said once:

Today’s boards are just not equipped to deal with today’s challenges. They don’t reflect the real world anymore. […] We have a problem… that with the urgency that we need to act right now, boards might become a bottleneck.

Why is sustainability a hot topic for boards?

As the world continues to recover from the COVID-19 crisis, the duty of businesses to engage in sustainable business practices for a better future has become more prominent.

Since the start of the pandemic, it has become increasingly evident that the duty to protect the human rights of communities is not only the responsibility of the state, but also of businesses. Even during an unprecedented health crisis, businesses are responsible for respecting labour rights and providing humane conditions at work. The COVID-19 crisis has reshuffled the cards on the societal role of businesses.

While respect for the environmental and social rights of the communities that companies operate in was always expected from a ‘rights’ perspective, it is now also a legal compliance imperative.

Human rights and environmental legislators – especially in Europe, the UK and the USA – are part of this broader trend and are increasingly calling on corporations to regulate their international supply chain, publicly report on their sustainable initiatives, and challenging instances of greenwashing.

Embedding good Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) systems in business operations has become the need of the hour. It is no coincidence that in recent years, the WEF Global Risks Report has consistently ranked environmental and social issues in the top five most critical global risks. The fact that ‘Climate action failure’ features first should come as no surprise.

Boards are feeling the pressure to change, especially given they are now legally liable and may be taken to court for failing to fulfil their legal responsibilities. Non-financial considerations now have economic implications. These challenges are here to stay; pressure is mounting on boardrooms to respond.

How have boards prepared for this?

Most of the world’s top companies have reacted via their sustainability reports and targets. Many have pledged to a net-zero carbon objective. However, very few actually provide the necessary details to accomplishing these ambitions The data reported by corporate climate leaders often lacks substance. Greenwashing is rife and, knowingly or not, many companies are overselling how sustainable they are.

One reason for this is a skill and knowledge gap, especially within companies’ top executive forces. This impacts the boardroom’s understanding and subsequent ability to address ESG risks. A recent survey by PwC found that only 27% of boards fully understood ESG risks.

Similarly, a joint survey by the Boston Consulting Group and the INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre found that only 47% of directors believe their board to have sufficient ESG competence. The survey also suggests a lack of knowledge on key sustainability issues like nature loss, climate change and human rights across all levels of the business.

This lack of knowledge has at the board level has severe implications. Boards personify businesses and the risk of greenwashing accusations increase when issues are perceived to originate from the top. If companies want to contribute to building a more sustainable society and avoid greenwashing backlash, they need the right expertise and skills at the top from the start. Companies must ensure that their board has members that have hands on experience working with sustainability issues.

Accepting responsibility without the relevant expertise

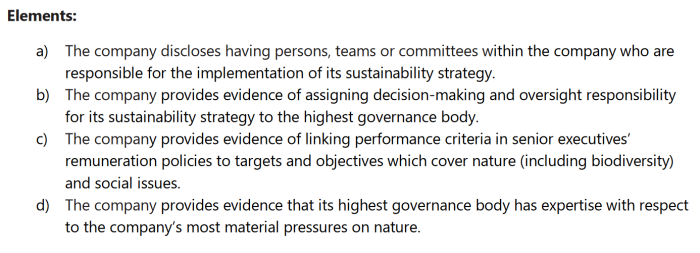

WBA’s Nature Benchmark looked into the governance structures of 400 of the largest companies globally. As part of the assessment, the indicator A2 (Accountability for sustainability strategy) examined whether companies have accountability systems in place for achieving their sustainable development objectives and targets – including whether companies’ highest governance bodies have expertise with respect to the companies’ most material pressures on nature (see below, element d).

While nearly 70% of companies in the Nature Benchmark assigned the responsibility for their sustainability strategy to their board, just 2% of boards actually possessed the relevant sustainability expertise on nature. This stark discrepancy is worrying as it highlights the fact that boards are accepting their sustainability responsibility without a clear understanding of what it actually entails.

What must companies do to demonstrate their board expertise?

While expertise can emerge from a group setting, it is fundamentally a deeply personal trait – an intricate mix of experience, training and technical knowledge.

Companies must ensure that that their boards have the necessary expertise to fulfil their responsibility by ensuring that at least one board member has expertise in this topic; demonstrated they had undertaken some kind of course or training by a certified organism; previous experience in specialised organisations such as consulting companies or NGOs; or having published reports and or supervised relevant studies.

However, a simple competency matrix is not sufficient if it is not backed by credentials or a detailed explanation. Similarly, experience needs to be specific as nominal elements, such as titles or membership to a committee, do not ensure competency. These precautions allow to avoid overstated claims of sustainability expertise – i.e. competence greenwashing, which is an increasingly prevalent phenomenon.

Moreover, board expertise must address the company’s most relevant sustainability topics to be effective. The most material issues for each industry are selected based on the latest Sectorial Materiality Table developed by the Science Based Target Network (SBTN).

They are issues that are key to evaluating companies’ impacts on nature and must be included in any value chain assessments. Examples can include climate, biodiversity, water, ecosystem conversion or hazardous waste. These topics are further complemented by an additional social element looking at expertise on issues such as human rights. In total, companies assessed in the Nature Benchmark generally have six or seven primary sustainability topics depending on their industries and specific products.

How can companies help bridging the board skill gap?

We ask companies to show relevant expertise on at least two-thirds of their most material sustainability issues, rather than in all of them. Acknowledging that boards may be limited by the number of their members, we also count external expertise if it is directly available to the directors. This could be specialised committee composed of external experts of which a board member is chairman. It must however be noted that the board will reap only as much benefit as the time and engagement it dedicates to such external structures.

The two main avenues for boards to gain relevant expertise are internal upskilling and, most importantly, through the incorporation of new sustainability profiles (board refreshment) into their ranks. A new internal equilibrium must be struck at the board level to shift from focusing primarily on financial matters, to engaging in a more balanced mix of financial and so-called ‘non-financial’ issues. Boards need to integrate the right strategic expertise into their composition so that they can effectively reflect today’s challenges, especially as the current polycrisis redefines and expands what they are accountable for.

It’s time for a renewal

Boards are meant to provide oversight and lead the corporate sustainability charge. However, many still lack the insight and foresight to do so. There is an urgent need for a renewal of the skills available to and within the board, be it from a legal or strategic perspective.

New profiles – beyond banking and accounting – are required at the top. Specialised committees, if implemented properly, can help provide this much needed sustainability expertise. They cannot, however, relieve boards from their duties entirely. There is no shortcut. Boards must rapidly adapt to their new role, lest they become an obstacle to their companies’ future.