Scaling up expectations: How to show serious action on tackling forced labour and recruitment fees

This blog is part of a series that focuses on some of the key changes to the revised methodology for the Corporate Human Right Benchmark, which was published on 30 September 2021. Julia Batho and Neill Wilkins from the Institute of Human Rights and Business outline the importance of the changes to the requirements regarding wage practices, as well as the new indicator regarding recruitment fees.

The Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB) has helped increase transparency and accountability on how companies address a range of important social indicators. Thanks to the CHRB, today global brands, investors and other stakeholders have clear criteria on which to assess human rights performance and measure progress. Comparisons with peer and competitor companies that CHRB provides can also be catalytic, providing impetus to greater company efforts to understand and respect human rights in business operations. It may also help reveal where effective governance by states is lacking, and encourage business to become greater advocates for improved regulation and enforcement.

The revised CHRB methodology indicates progress as well as growing expectations of what constitutes good business practice. The new indicators across a number of areas drill down deeper into key human rights and labour rights challenges and the steps needed to ensure they are appropriately addressed. What are the changes we find most notable?

First, the revised indicators on recruitment fees are noteworthy. It is no longer enough for a company to have a policy prohibiting the charging of recruitment fees to migrant workers – The Employer Pays Principle – in your direct operations and extended supply chains. This step alone is no longer exceptional.

What we see now is an expectation that companies demonstrate how they monitor and assess the implementation of that policy. Whereas previously a business might be able to point to a no-fee policy in their code of conduct, the CHRB indicator now asks for information showing how this is reflected in service level agreements and contracts with business partners and suppliers. Greater knowledge of workforces will be required: how many? from where? how were they hired?

Second, building on the previous CHRB methodology’s criteria regarding the reimbursement of recruitment fees charged to workers, greater transparency on company repayment programmes is now expected as well. This is a significant development and corroborates the increased focus on reimbursement of fees globally. Examples include high profile cases including Withhold Release Orders at the US border, as well as guidance developed by ethical trade consultancy Impactt and increased attention to the topic at this year’s Global Forum for Responsible Recruitment. As we understand more about what a repayment process involves for companies and workers, we hope this is one of those catalysing situations that leads to lasting reform. Having a repayment programme in place is commendable but companies should want to ensure the conditions that made such a programme necessary in the first place, won’t happen again.

Whereas previously a business might be able to point to a no-fee policy in their code of conduct, the CHRB indicator now asks for information showing how this is reflected in service level agreements and contracts with business partners and suppliers.

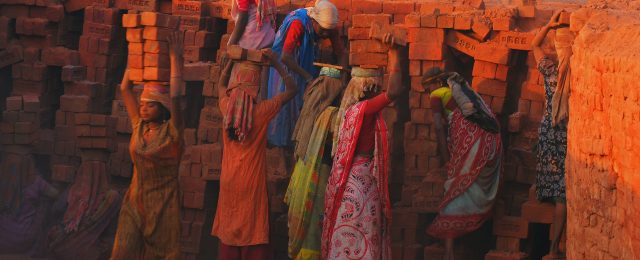

Third, the revised indicators on wage practice also emphasise the need for an increased focus on wage-related violations as a key entry point to address forced labour. Wage abuse – or wage theft – has become deeply embedded in how some businesses operate, particularly in labour-intensive sectors. Wage abuse can take the form of pay rates below the legal minimum, discriminatory wages, irregular/illegal deductions, and unpaid overtime, among other practices.

Addressing forced labour requires a clearer focus on how and why these abuses occur, including the labour rights violations that create an enabling environment for more severe forms of exploitation. Addressing the continual violation – or poor implementation – of labour standards is therefore crucial in the development of more practical and effective responses to forced labour. A more transformative approach to these issues requires looking at the ‘everyday’ vulnerabilities faced by workers, and not just individual cases of extreme exploitation.

The changes to CHRB’s Forced Labour and Recruitment Fee indicators are good examples of how the business and human rights agenda and the benchmark are maturing. It is important to stress, however, that no company should expect plaudits for taking steps that should be common practice anyway – even if their performance is better than others in their class. Respecting human rights and doing what is required according to internationally agreed standards is not a gift to be bestowed by business, it is a baseline expectation of all companies, wherever they operate.

Respecting human rights and doing what is required according to internationally agreed standards is not a gift to be bestowed by business, it is a baseline expectation of all companies, wherever they operate.

Perhaps these indicators are also a sign of another change that is slowly taking place concerning the language used to describe situations of exploitation, and how that language helps to shape our frame of reference. Forced labour and the charging of recruitment fees to workers sit squarely within a wider ‘modern slavery’ paradigm. The language of slavery and prevention of trafficking is often used to highlight the urgency of the situation facing many workers around the world and the need for change. However, exclusive use of this stark terminology has also sometimes diverted attention away from efforts to confront the broader continuum of labour rights violations, discrimination and unethical practices that lead to workers’ and migrant workers’ exploitation. Workers are too often portrayed as hapless victims who have little agency to make rational decisions on a reduced set of life options or who can advocate themselves for reform. Modern slavery becomes an aberration to the norm, and less acute – and yet much more common – abuses become normalised.

The revised methodology for the benchmark provides more indications for business on where progress is expected and the importance of being transparent about what actions are being undertaken to implement policy. In our own work with the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment, the Institute for Human Rights and Business is also strengthening its focus on the impact and implementation of policies on the ground. Reinforced by significant tools like the benchmark, this expectation will be shared by many other organisations working with business.

We should remind ourselves that none of the actions required to eliminate forced labour are unprecedented or particularly remarkable. It is about due diligence, respecting workers’ rights and addressing grievances. The recent changes to the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark’s methodology focused on policy-plus-action bring us closer to it’s purpose – to make human rights part of everyday business – because there should be nothing exceptional about that!

About the authors: Julia Batho is Head of Labour Rights and Neill Wilkins is Head of the Migrant Workers Programme at the Institute for Human Rights and Business.