Beyond net-zero: the rise of nature transition plans

Net-zero dominates sustainability talk. But as corporate’s climate transition planning becomes more structured, a parallel crisis accelerates: the rapid loss of nature and biodiversity. This isn’t just an environmental issue, but a material risk to business continuity. Thus, integrating nature into business resilience planning is no longer optional.

In our first blog of the Beyond net-zero blog series, we demystified Nature Transition Plans (NTPs) and introduced key frameworks. The big question for businesses now is: do we have enough tools, knowledge, and guidance to act on nature? The answer is increasingly ‘yes’.

In this second blog, we compare nature transition plans to climate transition plans to uncover current gaps, explore the tools available to close them, and highlight how leading companies are navigating the journey.

Getting started now matters more than ever; there’s no pathway towards any stable, sustainable future without companies changing.

Nature transition plans: spotlights and blind spots

What is a nature transition plan? As explained in our previous blog, a nature transition plan defines how you’ll align with global biodiversity goals like the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

Think of it like the climate transition plans you know (which map the journey to net-zero emissions through governance, targets, and value chain action), but focused on nature. The challenge is that a company’s impacts on nature, both from direct resource use and the external pressures their operations generate, are deeply local and complex. It isn’t as simple as measuring tons of CO₂. Losing a forest in Brazil isn’t fixed by planting trees in Canada.

Thus, recognising and understanding the intersections of a specific company with nature is a critical first step towards meaningful transitions. At the World Benchmarking Alliance’s Nature Benchmark, we reflect this principle in our methodology when assessing a company’s performance. Aligned with the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), we expect companies to begin their path by carrying out a diagnostic process: identifying and quantitatively assessing their dependencies and the impacts at their interface with nature. Then, businesses can better understand the physical, regulatory, and reputational risks they face, and identify opportunities for resilience, innovation, and long-term value creation.

Only once a clear diagnosis is established, companies are in a stronger position to develop a nature transition plan: one that reflects the company’s specific context and outlines a credible, actionable path to meet its nature-related goals. Notably, companies don’t need to have a fully developed nature transition plan in place before they can act or be recognised for their efforts.

Where to start?

Although WBA Nature Benchmark verifies the development of a nature transition plan with a standalone indicator, if companies address its key elements elsewhere, they are not penalised for lacking a formal plan. This flexible approach recognises the interdependence of climate, nature, and social issues, as the future demands integrating all these into one powerful, strategic plan for true resilience. And this plan isn’t just about conservation, it’s about securing your supply chains, resources, and long-term stability.

But how can we set meaningful plans towards a nature-positive future when no one has a complete picture of what that future looks like or a ready-built bridge to get us there?

Here’s the encouraging part: We’ve faced this kind of uncertainty before. A decade ago, corporate climate strategies were just as unclear. Yet today, net-zero roadmaps are mainstream. Nature transition plans are now echoing earlier stages of climate planning, but with climate’s lessons in hand, business are now better equipped to build resilience amidst uncertainty.

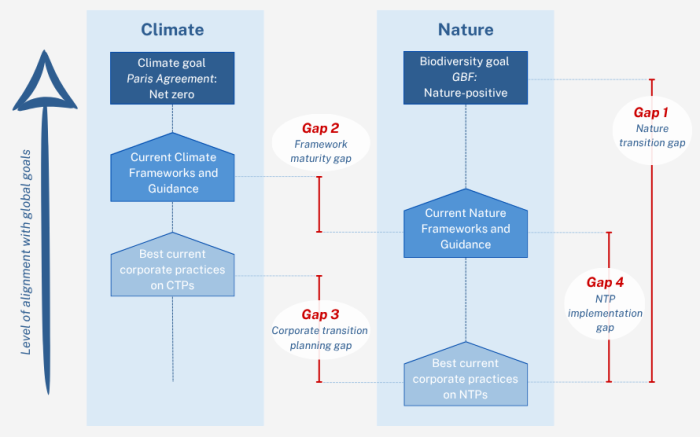

So, where do nature transition plans stand today compared to climate plans? What’s holding companies back on developing robust nature transition plans? The answer often boils down to a mix of methodological gaps (in data, methods, or evidence) and internal capability or priority issues. A side-by-side comparison of nature and climate transition plans from 10+ sector leaders, all of whom are top performers on biodiversity indicators in the WBA Nature Benchmark, makes this clear:

Overview of differences between notable corporates’ climate and nature transition plans

|

|||

| Methodological Gaps: | |||

| Aspect | Climate Transition Plans | Nature Transition Plans | Where to start |

| Strategic Maturity | Generally well-established, having evolved over more than a decade | Still emerging, with most companies in early or pilot phases; momentum has grown especially since 2020 | Leverage climate planning lessons (GFANZ, TPT) to accelerate nature planning maturity; apply WWF’s stepwise integration approach |

| Framework Alignment | Climate frameworks like the Paris Agreement, SBTi, and TCFD are widely adopted and mainstream | Alignment with nature frameworks such as the GBF, SBTN, and TNFD is still gaining traction | Adopt TNFD’s structure; apply WWF and GFANZ’s cross-framework mapping for consistent alignment |

| Target Setting | Companies typically set clear, quantitative, time-bound targets (e.g., emissions reductions) | Targets related to nature are often qualitative or early-stage, lacking consistent metrics and timelines. | Use SBTN interim targets and NPI State of Nature metrics to create time-bound quantitative goals (e.g., hectares restored, species richness) |

| Risk Analysis | Scenario planning (e.g., 1.5°C pathways) is a standard part of climate strategy | Scenario analysis for nature-related risks is just beginning to take shape | Pilot TNFD’s LEAP approach to explore dependencies and risks; refer to WWF and TNFD’s nature scenario guidance |

| Measurement Tools | Tools like carbon footprinting and emissions inventories are well-established | Nature-related tools (e.g., GBS, BIRS, Natural Capital Accounting) are newer and less standardized | Start with NPI’s draft State of Nature metrics and existing tools such as Global Biodiversity Score, refine as data availability improves |

| Organisational and Capability Gaps: | |||

| Aspect | Climate Transition Plans | Nature Transition Plans | Where to start |

| Governance Structures | Climate oversight is typically structured and embedded at the board level | Nature governance is often informal or emerging | Embed nature responsibilities into board and committee charters; follow GFANZ governance guidance on embedding accountability |

| Business Integration | Climate strategies are integrated across core business units and decision-making | Nature strategies are usually led by pilots or sustainability teams, rarely embedded company-wide | Adopt ACT-D to move from understanding nature impacts to business model transformation |

| Value Chain Coverage | Emissions across the full value chain (Scope 1, 2, and 3) are commonly addressed | Nature actions are often limited to own operations or pilots, ignoring broader supply chain impacts | Use TNFD’s value chain guidance to expand Nature-based solutions (NbS) and nature KPIs across value chains |

| Financial Integration | Climate plans usually tie into a company’s capital allocation and investment decisions (e.g., internal carbon pricing) | Financial mechanisms for nature (e.g., internal pricing, nature-related capital planning) are still rare | Use TNFD’s financial disclosure guidance to Incorporate nature impacts into risk assessments and capital allocation |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Strong engagement through cross-sector alliances like RE100 is common | Nature engagement is growing but often localized, project-based, or led by NGOs and civil society | Engage in multi-sector coalitions (e.g., NPI, TNFD adopters, GoNP! Pilots); build from project-based pilots to system-scale partnerships |

Companies crafting nature transition plans often show strength in high-level areas: recognising climate-nature links and setting aspirational goals like “nature positive” pledges or zero-deforestation commitments. Governance is also advancing, with biodiversity responsibilities increasingly assigned to sustainability teams or board committees, echoing the early days of climate governance. Sectors with legacy initiatives (e.g., fashion’s sustainable sourcing or food’s zero deforestation) leverage these as foundations.

But many of the challenges companies face aren’t due to a lack of available methods, but rather “perceived” gaps. A growing set of tools and frameworks already exists, and it’s now the time to build the knowledge and internal capability to apply them effectively. Targets, for example, often lack clarity, not because nature can’t be measured, but because many companies aren’t equipped to use the measurement methods and proxy indicators that already exist. The same applies to monitoring: progress is too often tracked through one-off case studies or anecdotal claims like “we planted 100,000 trees”, rather than through rigorous systems like satellite monitoring or third-party biodiversity audits to show whether actions are really working. Financial integration is limited too: biodiversity goals often sit outside core budgets, with little connection to investment decisions or incentives. And one important piece is often missing: people. Any serious plan must consider communities and livelihoods to ensure a just transition for nature.

As the comparison table shows, the structural maturity and integration of climate plans offer a useful benchmark for nature transition plans, but companies must accelerate the learning curve rather than wait for the same decade-long development path. Companies would do well to ask:

- Does our plan have clear targets grounded in science?

- Is it funded and tied to our core business decisions?

- How will we know if we’re tracking real impact and succeeding?

- And who should we partner with to fill our knowledge gaps?

By honestly answering these, businesses can identify where plans fall short, close the gap with existing tools, and update their approach as science evolves.

Three reasons to be hopeful

How are real companies translating this into action? Three companies - Ørsted, Hermès, and Cemex - are already demonstrating how businesses can integrate nature into their strategies, each with distinct approaches and lessons. Each company will have its own context and challenges, but the progression from awareness to a structured plan is one that all can follow. Ørsted, Hermès, and Cemex show that acting on nature is a journey: None have all the answers, but each is moving forward, learning and improving along the way, rather than waiting for perfection.

These case studies proves that nature transition planning isn’t one-size-fits-all. But they also illustrate that progress is possible across industries, whether renewable energy, consumer goods, or heavy manufacturing. Companies leading this charge from net zero to nature-positive won’t just mitigate risks, they’ll future-proof their operations in a world where ecological resilience is the foundation of long-term success.

To accelerate positive change, in January 2026 WBA is planning to update the Nature Benchmark and assess for the first time 2,000 companies on their sustainability impact — all at once. With that we hope to provide a guiding light to support and enable actions of companies, regulators, investors and stakeholders alike, with fact and insight as a beacon for progress.

With 2030 fast approaching, the time for hesitation is over. The tools are in hand, the expectations are set, and the opportunity is here. The rest is up to us.