Key finding

Most companies publicly prohibit violence and harassment in their workplaces, yet few take steps to prevent and remediate it

Violence and harassment abuses are prevalent in society, especially against more exposed groups such as women, migrants and young workers. This holds true for employees in the workplace. More than one in five people in employment globally have experienced violence and harassment at work, according to recent ILO research. In our assessment of 1,006 companies, we found that a majority of companies prohibit violence and harassment in their workplaces and have grievance reporting channels for their employees, though very few have a clear remediation process for addressing violence and harassment grievances. This gap is concerning given that prohibition policies alone are not sufficient to ensure that violence and harassment at work are eradicated. Companies need to have comprehensive policies and practices in place to ensure incidents are effectively prohibited, prevented, reported and remediated.

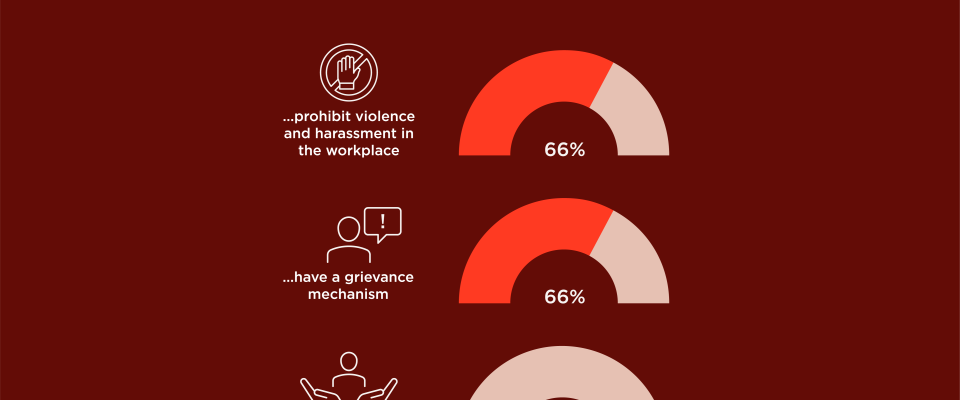

Violence and harassment in work contexts can take many forms, including physical, psychological and sexual. Certain behaviours are considered obvious abuses in most workplaces, such as hitting, restraining movement or unwanted sexual touching, while others might not be as evident, such as shouting, bullying or sexual comments. Two-thirds (66%) of the 1,006 companies have publicly available policies that prohibit violence and harassment at work. In our deep-dive assessment of companies within the apparel and food and agriculture sectors, we see that 67% of the 112 companies require their suppliers to do the same. However, we found that the companies which perform well on indicators covering violence and harassment prevention, reporting and remediation also include a more detailed definition of what they mean by the terms violence and harassment in their policies, as well as examples of behaviours that qualify as such. For a violence and harassment policy to be effective, it needs to clearly spell out what kinds of behaviours are unacceptable in order to rule out any possible doubt.

Gender-based violence is highly prevalent in the garment industry, and it is also used as a means of intimidation. Excessive overtime also affects women harder, as women often have to care for children and other dependents, and because of unsafe late-night commutes. Gender wage gaps are directly linked with a prevalent view of women’s work as less valuable; the social stigma around both gender-based violence and women speaking up for themselves means that the conventional auditing schemes used by brands are not up to the task of discovering and remediating these abuses. Which is why we need women-led, worker-driven alternatives.

– Paul Roeland, Transparency Coordinator at the Clean Clothes Campaign

Adequate reporting and remediation procedures are key to ensure that companies’ prohibition policies translate into practical tools. Violence and harassment offenses at work are highly underreported, often because either the process or the possible outcomes are not clear, or they do not cater to the needs of whistleblowers. According to the ILO, more than half of people who experienced violence and harassment at work said they disclosed the incident to someone else, and only half of these cases were reported to the survivor’s employer or supervisor due to fear for their reputation, or because they think it will be a waste of time or find procedures at work unclear. Most companies in our assessment publish their reporting channels for direct employees and for external individuals (66% and 55% respectively). However, only 4% of companies provide details about their remediation processes, including expected outcomes such as clear sanctions for perpetrators, and only half of those (2%) provide support to the whistleblowers, such as time off work or counselling, as a part of the remediation process. These poor results are consistent with the most frequently cited reasons for underreporting, namely a wasted effort, fear for one’s own reputation and unclear procedures.

Furthermore, companies might not even be aware of whether their remediation is effective for vulnerable groups, including women. Only 1% of the 1,006 companies collect, analyse and monitor sex-disaggregated data on the remediation of violence and harassment grievances. While confidentiality is essential to encourage employees to report abuses, it is possible for employers to gather basic demographic data about the whistleblower and/or the survivor without breaching such confidentiality. In fact, in order to ensure follow-up and remediation, reporting channels already require basic details about the person submitting a claim given that anonymous reports cannot be resolved in a personalised manner.

Alongside having a clear remediation process with predictable outcomes and protection for the whistleblower, companies can take other actions to prevent violence and harassment from happening in their workplaces. In our deep-dive assessment within the apparel and food and agriculture sectors, we found that 23% of the 112 companies have dedicated trainings for their employees, and 13% implement other additional actions on violence and harassment, such as providing specialised support to employees who are facing domestic violence. Some of these companies also aim to prevent violence and harassment in their supply chains by requiring their suppliers to make their violence and harassment policy available in multiple languages (6% of the 112 companies) and requiring them to provide trainings to their managers and workers (10% of 112 companies).

Effective systems to tackle gender-based violence and harassment at work include a comprehensive approach: prevention through policies and actions, safe reporting channels, clear grievance resolution mechanisms with support for whistleblowers, and monitoring of the remediation outcomes. Policies and practices to prevent and address abuses should create an enabling environment where all individuals, especially the most vulnerable, feel encouraged to report. In situations involving distress or where there may be fear of repercussions and retaliation, workers should have a clear path to follow as well as certainty that they will be protected and that their grievance will be resolved. For this to happen, all companies should go beyond prohibition of violence and harassment and step up their game on remediation, while requiring their suppliers to do the same.